The Days That Broke the Calm

As October closes, the full scale of Tanzania’s post-election crisis remains unknown. The number of the dead and detained is contested, yet the weight of grief and fear is palpable across the mainland and beyond, including in Kenya at the Namanga border, where violence has spilled over and families cross seeking safety. Hospitals in Dar es Salaam and Mwanza are said to be overwhelmed, and the country remains largely offline under one of the most extensive internet blackouts in its history.

The events that have plunged Tanzania into its gravest political turmoil in years did not begin on election day. They are the culmination of months, perhaps years, of tightening control by the ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), over the machinery of the state.

By early 2025, the political temperature was already rising. Opposition parties, civil society groups, and journalists reported escalating restrictions. In April, Tanzania’s High Court upheld a controversial electoral commission ruling that barred the main opposition party, Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (CHADEMA), from participating in the general election, citing “technical irregularities” in registration. Opposition leaders denounced the decision as an “engineered one-party election.”

Over the following months, the clampdown deepened. Independent outlets like The Citizen and Mwananchi chronicled a series of arrests and disappearances of activists and journalists in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma. In June, regional alarm spiked when Kenyan photojournalist Boniface Mwangi and Ugandan lawyer Agather Atuhaire alleged abduction and torture by Tanzanian security agents. Both were released only after diplomatic pressure.

As the October polls drew closer, opposition activity was systematically curtailed. CHADEMA chair Tundu Lissu, recently returned from exile, was arrested on charges of “incitement and treason.” His deputy, John Heche, was taken into custody in what authorities called “a preventive measure.”

Religious institutions, too, were drawn into the dragnet. MP-pastor Josephat Gwajima’s church was deregistered and its accounts frozen after he criticised the government from the pulpit. Public gatherings became rare. By mid-October, most of the opposition’s visible leadership was behind bars or in hiding.

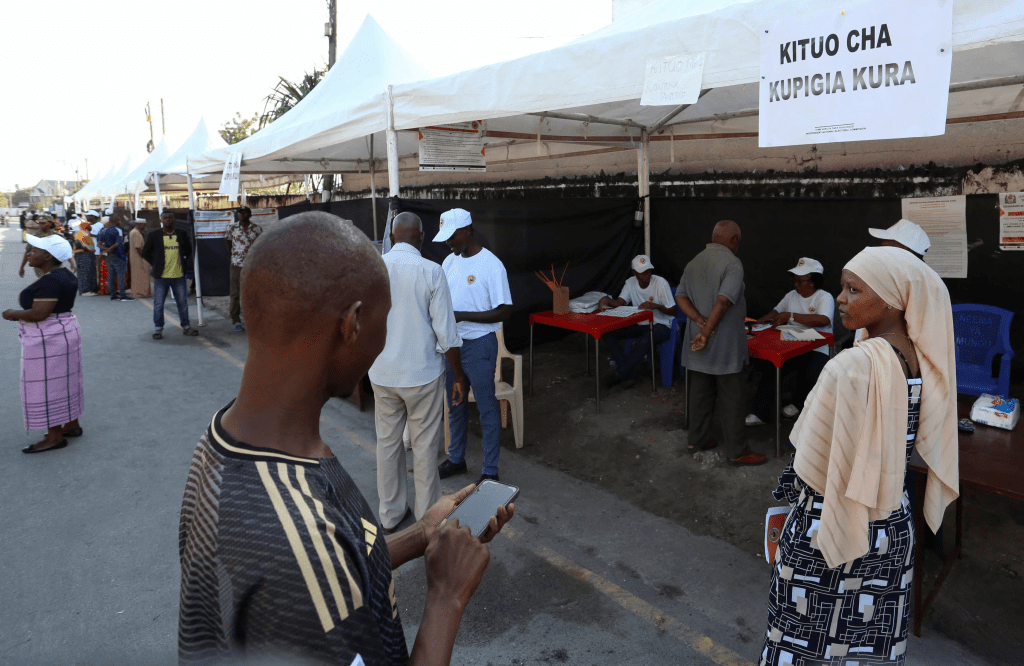

On October 29, Tanzanians went to the polls amid heavy security. Reports from Mwananchi and other local outlets described late openings, missing voter rolls, and widespread intimidation. Several election observers were denied access to polling stations. Internet slowdowns began that morning and hardened into a full shutdown by midday.

Late that night, the National Electoral Commission declared a near-total victory for CCM — over 95 percent of the vote — securing another term for President Samia Suluhu Hassan.

Within hours, protests erupted in Dar es Salaam, Mwanza, Arusha, and Dodoma. Crowds chanted for a rerun of the election and the release of detained leaders. Security forces moved swiftly and brutally. Eyewitnesses told The Citizen and Kenya’s The Standard that police used live ammunition and chased demonstrators into schools and hospitals.

By dawn, hospitals were overflowing. Mwananyamala and Muhimbili hospitals in Dar es Salaam reported hundreds of casualties; Bugando Hospital in Mwanza was said to have reached full capacity. Yet casualty figures remain impossible to verify under the ongoing communication blackout.

On October 30, the government imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew. The Ministry of Information dismissed the protests as “isolated disturbances instigated by criminal groups backed by foreign sponsors.” Opposition figures countered that it was “a people’s uprising against an illegitimate regime.”

The blackout has rendered the crisis almost invisible. The United Nations cited “credible information” of at least ten deaths, while opposition sources claim more than seven hundred, including three hundred fifty in Dar es Salaam alone. Hospitals have been instructed not to release casualty data, and local journalists face intimidation or arrest for attempting to report.

By October 31, soldiers patrolled the streets of major cities, enforcing curfews and suppressing vigils. Small groups of citizens continue to light candles for the dead. While the government insists that order has been restored, fear and silence hang heavy in the air.

Across the border, Kenya and Uganda have tightened security amid fears that the violence could spill over.

International reactions have begun to gather force. The African Union and United Nations have called for restraint, while Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have condemned the killings and detentions. Western governments have expressed concern over what they describe as “a severe contraction of democratic space.”

But within Tanzania, the silence remains nearly total. A nation that once prided itself on relative calm and dialogue now finds itself locked in both a digital and moral isolation.

As October gives way to November, East Africa stands at a threshold. The number of Tanzania’s missing and dead is still contested; the truth of what has unfolded is still buried beneath state secrecy and shutdown. What is not in dispute is the rupture — a sense that something foundational has been broken.

At the Namanga border, a mother tells Kenya’s The Nation she has not heard from her son since election night. “He voted and never came home,” she says, her voice drowned out by the rumble of trucks heading north. “Now we wait. Only God knows what has happened.”

The waiting — like the silence — stretches on.